Aristotle and Alison Discover the Secrets of Their Dads

By Emma Carlson '22

ENGL 216: LGBTQ+ Literature and Culture

Emma wrote this paper for the final project assignment in LGBTQ+ Literature and Culture. She chose the option to respond to at least two of our course texts through a creative medium, then provide an explanation of her response.

-Valerie Billing

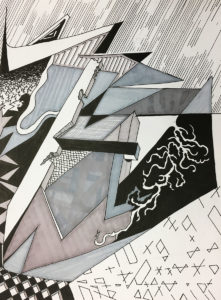

for smoke and mirrors (Alison)

maybe i didn’t inherit

your eye for aesthetics

for smoke

(mirrors and) (and mirrors)

but you made of me

a magician

still.

maybe not the exact same kind as you,

but a magician

still.

we know a good trick

when we see one,

don’t we, dad?

we also know

when we can’t

oil the cuffs,

when we are no

harry houdini,

when we confine,

when we cannot

break out

and breathe

so i make you

and you make me

and we live

vicariously.

it’s your last act

that’s landed

no one knows how

why

you vanished

they have their theories.

but they don’t know.

not like i do.

do i know?

you have made yourself

inimitable

in your curiosity

you have secured your seat

amongst roanoke

and ufo’s

and life’s great mysteries

…

you strolled before a sunbeam

and bursted into light

light that crawls across mom’s stage,

through the theatre of our family

to the few and far between failures

of your facade

and i want to call you a fucking fraud how dare you

force me beneath the blinding bulbs of grief of a

premature memoir

of making your show mean something?

‘cause you were shit, dad.

shit at guessing cards,

at getting the bunny

out of the goddamn hat,

at knowing whether or not

you had us fooled.

but we’re both shit magicians

in the end:

we reveal our secrets

for just a second of being seen;

pulling back the curtain,

revealing the fakes

and, worse still,

the reals.

dad.

you didn’t stroll before a sunbeam

because mom got the guts

to leave this decrepit performance.

right?

no.

that was a long time coming.

you knew that.

you had to know that.

no.

you strolled before a sunbeam

because you ceased to amaze.

my own war (Aristotle)

i’ve never been

to Vietnam.

mom says

it was real bad.

mom also says,

“your father was beautiful”

like that’s supposed to make sense.

beautiful how?

an impermanency, certainly.

but beautiful like adonis?

like dante?

more likely, i think

and all i do is think

is you were beautiful

as a baby is;

just a big-eyed bambino

who saw something too

violent.

maybe ‘copters c R as h i n g,

Cutting.

ensue the carnage and chaos and

(how does it feel

to house a whole other country

in your head?)

i can’t find you

and i’m always looking for you, dad

under the monsoons

you never mentioned.

and the water reeks of chlorine,

of dante,

of my own war.

don’t ask me about him.

please.

i don’t know how i’ll answer.

i don’t know if i’ll be silent

like you.

i’ve got bambino eyes, too.

how long

‘till i’m ugly?

how long

‘till i only see the rain?

i’m afraid we are different.

is no one else ashamed?

is no one else alone?

i’m afraid we are the same.

am i doomed as the soldier?

will i ever come home?

will dante, too, tell my kids,

“he was beautiful”?

will dante, too, pretend

i’m coming home?

As popular stand-up comedian John Mulaney once dryly remarked in a special: “None of us really know our fathers” (Mulaney). And while it was said in the spirit of morbid comedy, it also rings a little true. For better or for worse, there exists an ambiance of mystery in many father-child relationships. This ambiance can be further complicated by the father and/or the child being queer. In Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and in Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s novel Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, parenting—particularly parenting by the father figure—plays an essential role for the main characters’ development of their queer identities. Aristotle and Alison’s queer identities enable them to ultimately better understand their dads and have their dads better understand them, arguably more fully than they could if they weren’t queer. To illustrate this theory, I have written two pieces of accompanying poetry. The intent of these pieces is to speak to how queerness can be a vehicle for both father and child to better empathize with and accept one another for who they are.

The first poem, titled “For Smoke and Mirrors,” depicts Alison, a college-aged butch lesbian, as she struggles to understand the complex similarities between herself and her queer father. Primarily, the piece depends on the metaphor of magic. This choice was loosely inspired by Alison’s stinging comment on the manner in which her father exercises his artistic abilities: “He used his skillful artifice not to make things, but to make things appear what they were not” (Bechdel 16).

Through their interactions, it’s evident that Alison and her father use each other as a medium for expressing aspects of identity forbidden to them.

Much like a magician, Alison’s father specializes in deceit and concealment. Alison, attempting to survive in the world as a fellow queer person, models his behavior. I observe this in my piece, writing from the perspective of Alison, “maybe i didn’t inherit / your eye for aesthetics / for smoke and mirrors / but you made of me / a magician / still” (1-6).

Through their interactions, it’s evident that Alison and her father use each other as a medium for expressing aspects of identity forbidden to them. For instance, Alison recalls getting into frequent disputes with her father over what the other should wear. She remarks, “While I was trying to compensate for something unmanly in him, he was trying to express something feminine through me… I wanted the muscles and tweed like my father wanted the velvet and pearls—subjectively, for myself” (98-99). It’s not an ideal situation for either party. As many queer people are, they’re accustomed to compromising their identity for the sake of social acceptance, so they understand the necessity of living their truths through one another.

At first, Alison doesn’t directly admit she wants the masculine clothing for herself. Like a magician ducks behind a curtain, she hides behind what she feels is the obvious shame of her overly feminine father—something anyone, queer or not, might be embarrassed of. Back to the main point, Alison and her father, for the most part, understand why they want one another to appear a certain way. I reference this in my lines, “we know… / when we are no / harry houdini / when we confine, / when we cannot / break out / and breathe / so i make you / and you make me / and we live / vicariously“ (11-26). Just as magicians, contortionists, and escape artists must be aware of their physical limits, Alison and her father must be wary of the social limit to their self-expression or, in this metaphor, their act. Though they are personally constrained, they can still perform through, and subsequently better empathize with, each other. Had either of them been heterosexual and cisgender, this give-and-take never would’ve worked. Since they both have a fairly good grasp of what it feels like to have one’s identity caged in, this vicarious behavior is permissible between them.

The second poem, titled “My Own War,” is written from the perspective of Aristotle—a fifteen-year-old boy who is frustrated by his inability to see what his mom sees in his dad, a Vietnam veteran suffering from PTSD. Aristotle also fears that as he endures his own internal war, he will follow in his father’s footsteps by becoming removed from those who love him. Since he was very young, Aristotle can remember attempting to understand his father’s distance and subsequently becoming angry when the answers were dissatisfying. He recalls a charged conversation with his mother in a fit of fury after his father wouldn’t play with him: “‘How could you have married that guy?’… ‘Your father was beautiful.’ She didn’t even hesitate. I wanted to ask her what had happened to all that beauty” (Sáenz 12). Obviously, a haze of indignation and childish hurt is clouding Aristotle’s judgment, but even though he phrases it cruelly, he’s genuinely trying to comprehend his parents’ thoughts. This is something I reference in “My Own War,” as I write: “mom also says / ‘your father was beautiful’ / like that’s supposed to make sense. / beautiful how? / … / beautiful like adonis? / like dante?” (7-13). By attempting to see his mother’s perspective by applying it to his own queer experience of loving another boy, Dante, Aristotle can then better cut through the confusion of how his mom and dad came to be together.

But there’s a much bigger topic at play in this poem. Arguably, war is one of the biggest themes of Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe. The obvious example of war is the one that Aristotle’s dad fought in. Aristotle did not fight in a war like his father, but he is a veteran in his own right. Though he doesn’t always realize it, Aristotle is constantly battling with himself—particularly when it comes to Dante. This is something I attempted to capture in Aristotle’s brief but cutting remark in my poem: “how does it feel / to house a whole other country / in your head?” (24-26). This is meant as a cruel jab, but there’s a genuine question beneath the malicious surface. Does it feel like how Aristotle feels? Is Aristotle an alien compared to how everyone else functions?

Throughout the novel, Aristotle experiences a disconnect with other boys his age. Unable to identify with them, likely because of his queer identity, he searches for grounding in his father. I allude to this search in “My Own War” as I write, “i’m afraid we are different / is no one else ashamed? / is no one else alone? / i’m afraid we are the same. / am i doomed as the soldier? / will i ever come home?” (44-49). Aristotle fears he is entirely unique (and thus incomprehensible) while simultaneously fearing he’s too much like his father. The apprehension of following in his father’s footsteps creates a tense, inner conflict about what he truly wants.

In seeking to understand the battle scars and emotional baggage of his father, Aristotle unearths his deepest, most uncomfortable truth: he’s been carrying his own war, his own unspeakable country, all along. He remarks as much after discussing it with his mother and father, thinking, “All of the answers had always been so close and yet I had always fought them without even knowing it… My father was right. And it was true what my mother said. We all fight our own private wars” (Sáenz 359). Out of shame, both Aristotle and his father bury their conflicts. Shame, an emotion frequently present in the young queer experience, is easy to underestimate in terms of emotional impact if not endured firsthand. So, had Aristotle not employed his queer experience to empathize with his dad’s embarrassment and trauma, it’s unlikely that Aristotle would have come to this realization. Following their confession session, Aristotle freely admits to himself, “For once in my life, I understood my father perfectly. And he understood me” (350). It’s from Aristotle’s romantic love for Dante that this mutual empathy is discovered. Such an intimate moment of vulnerability would have been much less organic and significant in a heterosexual setting, as Aristotle would feel no shame and thus be unable to understand why his father kept himself so distant.

Before making my concluding statements, I would like to address the purpose behind the unconventional formatting of my poetry. I took heavy inspiration from Trish Salah, an Arab-Canadian poet who writes with a style that can only be described as queer. Such as Salah does in her poem “Wanting in Arabic,” I wanted to toy with abrupt line breaks, sentence fragments, and abrupt stops. These elements, when obscurely broken, cultivate a more accurate representation of human thought and experience than when they’re held in respect to such an established format as a Shakesperian sonnet. Following Salah’s blazed trail, I held more freedom to candidly explore the father-child relationships of Aristotle and Alison.

So why does any of this matter? What significance is it that queerness holds the potential to be a vehicle for which parents and children may arrive at better understandings of one another? In short, it matters because of the immense prevalence of the misconception that indicates otherwise. Often, non-straight, non-cisgender individuals are blamed for being inconsiderate to others’ negative reactions to their mere existence. We then attempt to make ourselves more palatable, denying any flamboyance, out of fear we’ll be called callous or indifferent. But, we are suffering for a trait we don’t possess. As is evident through the stories of Aristotle and Alison, for many reasons, the queer path is a difficult one to take. Precisely because it is so difficult, we foster a lasting empathy for all things different and all things that make people feel ashamed or afraid. Why wouldn’t we, when we know firsthand just how awful it feels? Of course, it’s fair to say that I’m overgeneralizing here. Not all queer people have this outlook, nor should they feel obligated to develop it. But more than enough of us are better equipped than our heterosexual, cisgender counterparts to take on the complex task that is understanding our parents for the people they honestly are. And, on the likely chance that they’re worthy, accept them, too.

Works Cited

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

Mulaney, John. The Comeback Kid. Chicago, Illinois. 2017.

Sáenz, Benjamin Alire. Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe. Simon and Schuster, 2012.

Salah, Trish. “Wanting in Arabic.” Wanting in Arabic and Poems, TSAR Publications, 2013.