And It Was a Loop

By Sarah Linde ’24

ENGL 213: Nature Writing and Environmental Literature

The class and I appreciate Sarah’s “And It was a Loop” with its theme of the circles of life and death and the way she integrates herself into the loops. She marvels at the ephemeral snowflakes and spring flora and the enduring loops of life. Her creative description, word choice, and perspectives draw readers into these circles with the gliding reassurances of natural patterns, layers, dimensions, and wonders.

-Mary Stark

There is a forest behind my house, just north of Pella. It is not so much deep, as it is wide. A gentle circle of embrace curled around the homes of my neighbors and myself. Nature is full of loops, whether it be the formation of trees, or the way familiar Cathartes aura (turkey vultures) swoop and glide across drafts that keep their wings free of the green summer canopies.

The forest is a place I grew up, and it is a place I will always return to. The constant march of my footsteps, along with those of my kin, wear a trail in the placid earth. Our boots and bodies push back branches and crush down shoots as we carve our place in this world. Fret not, though, for the wild plants and growing trees, for the cut we make is that of a sharpened blade: clean and smooth. And though our mark is long-lasting, it is far from permanent. When we are gone the forest will heal over this path we left. Branches reaching across it, flowers and bushes climbing from the fertile earth.

Until that day comes, we tread carefully enough, sticking to the path in the leaf-litter earth that we have long since cleared, leaving the rest of the forest to its own devices. The ground on which we walk is made up of layers- one for each year I have been alive, with countless more from the years before that. And when I am finally gone and buried under the layers of a different part of the earth, this place will still have countless layers left to create. Leaves fall, they lay on the cold winter earth, the world tilts and warms and the leaves slowly decay into compost. I’m not sure how long it takes for a single leaf to fully rot.

As a child, I assumed they were the same leaves all year long, every year I visited. Now, I can’t help but think of what Joan Maloof wrote, about how, “[Trees] fertilize themselves with their own rain of debris” (Maloof 132). Another cycle- that of life and death and rebirth, told across tens of hundreds of years.

As children, my siblings and I were only allowed to walk into the woods when our father accompanied us. We’d save these trips for when the weather was the most appropriate, be it the warm touch of spring or the gentle chill of autumn. Autumn walks were a treasure of sensation; leaves would rustle as they were pulled loose, falling and dancing upon the air and sometimes catching on a jacket or hair. The scent of gentle decay that I so heavily associate with the season would surround us in a way that could practically be tasted. Despite the cold slowly creeping in, birds would still flutter in the branches if you looked closely enough. It was as if they were acting in defiance to change, saying that even in this state of half-death, their home would stay alive and vibrant for ages to come.

Returning to the forest for the first time in the cold grip of January felt alienating, to say the least. The forest is nothing but a skeleton of its former glory, a husk of the things it once held. There are no birds in the trees, and no leaves to grace their branches. The branches rattle together in a death-toll, in contrast to the familiar rustle they offer when they are covered in leaves, whether it be leaves of yellow-red-orange or a bright healthy green. Trees are unique in that way, though. Their leaves will not remain gone forever, they will grow back new and fresh, and the cycle of death and rebirth will continue until each tree reaches its own eventual end. With that mindset, it’s difficult to be too sad about the forest’s current state, especially not when winter can be beautiful in its own way.

Frost bites dead leaves, creating delicate patterns that melt under a warm touch. Soon, the sun will come in full force and destroy those intricate patterns of ice; like they were never there to begin with. And yet, I think beauty can be appreciated, even if it is fleeting. Snowflakes are much the same, and when they catch on my gloves or coat, I always take the time to try and see the delicate structure before it liquifies into nothing. Sometimes, when the flakes are large, I am lucky enough to see. Other times, the little specks of white seem to be nothing but dots, and their design is forever lost within moments.

Still, as January fades into February fades into March, I can’t help but dream of spring, and think on the words of poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. “And Winter slumbering in the open air/Wears on his smiling face a dream of Spring!” (Coleridge 3/4). Perhaps then, the world dreams as I do of the shift in seasons. Perhaps it longs to ease back into the life and bursting color spring brings.

Spring was another common time for my family to tread the woods. Slick mud and flowers being some of the most obvious things the season brings. The mud was a bit of a hazard to walk through, and I definitely remember slipping more than once, but it was worth it for those flowers. Dozens of bright blooms pop up in early spring, stretching up towards the sun as it leaks through the branches that are still not quite coated.

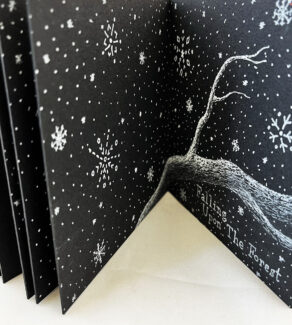

Gunner Hutton – Artist’s book, detail 2D Problem Solving

Mertensia virginica (the Virginia bluebell) and Dicentra cucullaria (Dutchman’s breeches) were always some of my favorite flowers to pick and bundle into a scrappy bouquet for my mother. She’d always humor me, putting them in a glass of water to try and keep them alive for a few days more. But eventually the flowers would wilt and decay, just like the leaves as they fall from the trees, just like any other living thing. In the past we’d toss our food waste in a pile near the edge of the woods, letting raccoons and possums take what they pleased before bacteria and fungi did the rest. With that food waste would go my plucked flowers, and I look back and wonder, like Walt Whitman did, “O how can it be that the ground itself does not sicken/How can you be alive you growths of spring…Are they not continually putting distemper’d corpses with you/Is not every continent work’d over and over with sour dead?” (Whitman 6/7, 9/10). For the compost we offer is nothing more than those things the earth once grew, and whether it be little hands that clumsily beheaded flowers, or skilled ones that brought down fruit, the world still ends up bringing its own living back into the dirt as they pass. A loop of life and death we see again and again in nature.

Just as spring is upon us now, summer will bear down soon after. I’ve never been during that time, when the sun is hot and the forest is in its fullest greens. It is then that the Turkey vultures I love to watch are most active, dancing on the wind and circling in search of something to pick apart. Perhaps this year, I will explore the woods during this time and get to know the sounds and sights while they are there. After all, just as the seasons cycle and loop endlessly, I too will loop between the places I am headed and this place where I grew up. I will return, again and again, and create my own loop. My own addition to the nature of this place.

Works Cited

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Work without Hope by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43999/work-without-hope.

Maloof, Joan. Teaching the Trees: Lessons from the Forest. University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Whitman, Walt. “This Compost.” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, poets.org/poem/compost.