To My Core

By Sarah Smith ’25

LAS 110: Intersections

The final project in my Intersections class asked students to try their hand at writing a poem and then to write a paper explaining their artistic choices. Sarah’s poem is both raw and beautiful, using sound, rhythm, and vivid imagery to create emotion and demonstrate the power of language in processing trauma. The accompanying paper is compellingly written, guided by clear arguments and substantial evidence that walk readers through key lines in the poem and show in-depth connections with two poems we read in class that inspired Sarah’s use of language and imagery.

– Valerie Billing

To My Core

time

a weightless concept

the flutter of a butterfly’s wings

the scream of tires on asphalt the soft thud of earth atop a mahogany casket

the decrepit hands of time

braid my hair with a manufactured sense of hope

renewed happiness

the eyes that once wept

the hands that once gripped the clouds for a ride

away from the stay

here at hotel hell

anew

i cut myself open

the wounds still fresh

blood making rivers in the divots of my fingertips

my intestines hang out where they shouldn’t be

out from my core

vulnerable

slewing down by my vagina

where they shouldn’t be

reminding me that i am both human and woman

mortality screamed into my eardrums

painted across my face

a picture lost in translation

a happy girl

a promising future

skin as thick as sun washed leather

and a heart as solid as earth’s core

your face forever planted

under the big ‘O’ in obituary

a picture lost in translation

dirt caked underneath my fingernails

trying to dig you out of earth’s core

d back to mine

formaldehyde fingers

an abdomen stuffed with cotton

almost human

want to puke but the hole in my stomach won’t let me

time

home for my broken soul

my nose scrunching for its smell of nostalgia

like a coke addict

no more

nothing to touch

nothing to see

nothing to hear

nothing more than a concept

the grass beseeches my knees

asking for time of departure

in no more than a whisper

i beg the sparkling stone for something more

This poem is a dramatized version of a real event that happened in my life. I lost my serious boyfriend last year to suicide. While talking and writing about his life, death, and memories is something that isn’t difficult for me to do and is something that I have done quite frequently, this is the first time I ever wrote about him being dead in the ground, focusing on him as a carcass. This concept may sound morbid or vulgar, but it was honestly so healing for me. Throughout my poem, I really tried to focus on his remains: “formaldehyde fingers / an abdomen stuffed with cotton / almost human” (Smith 36-38). I didn’t think of him as a human or of my memories of him during his life. Rather, I thought of him as a body that has been in a funeral home. I thought of him as a body that is cold and dead and void of a beating heart or a working brain. Writing about him being a dead body in my poem made it easier to metabolize that idea for me. It took power away from that ominous thought of his death and made it feel more human and normal.

Being sad is normal, too. Being sad about his death isn’t a new concept in my writings either, but the way that I addressed it in this poem is. Before, I always wrote about my sadness as big and profound, a placeholder for the newfound happiness and growth I would receive as time inevitably heals my wounds. I never wrote about how ugly and humiliating it is, though. I never addressed what it’s like to scream at a stone in the ground for hours on end, or to fall asleep cuddling a patch of grass in a cemetery because it’s the only place I feel calm. In my poem, I discuss the feeling of helpless desperation that death sometimes brings: “dirt caked underneath my fingernails / trying to dig you out of earth’s core / and back to mine” (Smith, 33-35). In these lines, I tell the urgency that my body felt to bring itself back to what used to be normal, sometimes digging at the ground to just feel a little less far away from my loved one and that sense of normalcy.

Though my poem is different, it still has the same connotation of sadness that Emma Carlson’s poem For Smoke and Mirrors did. In lines 49-51 of Emma’s poem, she writes about some of the sadness and anger that is forced upon the loved ones of someone who died by suicide: “and i want to call you a fucking fraud how dare you / force me beneath the blinding bulbs of grief of a / premature memoir” (Carlson 49-51). I like these lines because, though I didn’t write about the anger that comes with grieving someone who died by suicide, we both discussed taboo subjects that aren’t always well received. The subject she discussed was being angry at the dead loved one and mine was being open about thinking about and discussing them as a carcass and not just as a memory. Though I didn’t write about the same topic in my poem that she did in these lines, they still resonated with me and my own grieving journey. This made her poem feel more intimate to me and my story.

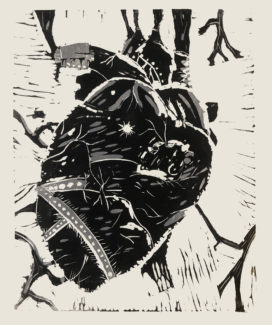

I found inspiration through the expression of vulnerability sometimes discussed in Emma’s poem: “we reveal our secrets / for just a second of being seen; / pulling back the curtain” (Carlson 61-63). I perceived these lines as the breaking of a facade that is held up by those who are dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts. When someone with depression completes suicide, they’re letting everyone in on the secret life they’ve been keeping from them, letting them see the complete identity of who that person was. I expressed this vulnerability in my poem: “i cut myself open / the wounds still fresh / blood making rivers in the divots of my fingertips / my intestines hang out where they shouldn’t be / out from my core / vulnerable” (Smith 14-19). The message that I was trying to convey in these lines was the ugly, messy, and inevitable vulnerability that comes from expressing one’s grief for someone who died by suicide. I screamed and cried out loud in the cemetery, whether there were people there or not. I made my pain very transparent and allowed other people to see my messy journey. Because my boyfriend broke his facade and allowed everyone to see the truth of his depression by completing suicide, it broke my facade, too. I allowed his wounds to bleed over into my life, and I allowed them to perpetuate my hurt. I used the metaphor of my stomach being cut open and my intestines hanging out of me because that is how loss feels. I always describe the feeling I felt when I first found out my boyfriend passed away as my stomach falling out of my body. I felt a rush of adrenaline fill my body in a second and then leave just as fast, taking everything with it and leaving me feeling empty. I wanted to use these feelings as inspiration for some lines in my poem.

I was also inspired by the poem Living in the Body by Joyce Sutphen. This poem inspired the aspects of my poem that talked about the physicality of the body. Though concepts like happiness and self-esteem were talked about in her poem, I focused on the parts that talked about the body: “Body is a thing that you have to leave / eventually. You know that because you have / seen others do it, / others who were once like you,” (Sutphen 17-20). I liked the wording in these lines. It brought about a sort of intimacy that is sometimes faced with death. Not only do you see loved ones die, but because you know that they have passed, you have the assurance that you will someday also. The way those lines brought about a connectedness with loved ones and death, inspired some in my own poem: your face / forever planted under the big ‘O’ in obituary / a picture lost in translation” (Smith 30-32). These lines took more of an intimate approach, speaking to my loved one as if they were alive, rather than speaking about them and the morbidity of their death. This connected life and death in a similar way that Sutphen’s did.

Other lines in her last stanza took a much more physical approach when focusing on the body: “living inside their pile of bones and / flesh, smiling at you, loving you, / leaning in the doorway, talking to you / for hours and then one day they / are gone. No forwarding address” (Sutphen 21-25). This quote talks about the “pile of bones and flesh” and the fact that one day they are with you and the next they are gone with “no forwarding address”. They discuss the memories that are attached to the body. These lines talk about the same aspect of death that my poem did. Though this inspired the essence of my entire poem, it helped with some specific lines: “time / home for my broken soul / my nose scrunching for its / smell of nostalgia / like a coke addict” (Smith 40-43). These lines are really the only times I talk about the typical things that are discussed when it comes to missing someone, memories, and nostalgia. These lines are my way of attaching a soul and a mind to the body and allowing myself to wallow in the positivity of what used to be and who used to be.

Though people write for a multitude of reasons, writing this poem was healing for me. I allowed myself to think about my boyfriend as an actual dead body in the ground rather than fantasize about the memories attached to him. It was difficult sometimes but attaching it to other works of poetry really made me feel less alone, even if the poems were not about the same topics as mine was.

Works Cited

Carlson, Emma. “Aristotle and Alison Discover the Secrets of Their Dads.” The Writing Anthology. Central College, 2020.

Sutphen, Joyce. “Living in the Body.” Poetry Foundation, 1995, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51337/living-in-the-body