Restoration Through Brave Narration

By Peyton Gray '18

ENGL-361: World Literature I

Peyton positions her reading of The Thousand and One Nights in relation to both feminist and historical scholarship. Her reading of the Nights considers the collection’s original cultural context to make an argument about its protofeminist potential in its own time and its ongoing feminist potential in ours.

–Valerie Billing

In the popular Middle Eastern piece of literature entitled The Thousand and One Nights (The Nights), a frame-tale narrative is used to tell various stories that revolve around King Shahrayar and his relationship with women. The Nights begins by describing the king’s view of his wife’s betrayal and through this event, the main plot is uncovered. For the next few stories, the king and his brother go on a journey to find someone else who is affected by this betrayal just as they are. When the king does, indeed, find someone in a worse situation than himself, he returns to his kingdom and declares that he will sleep with a virgin every night, and, in order to mirror his perception that women are dangerous and should not be trusted, he will murder her the next morning. It is through this idea that the character of Shahrazad is introduced, the brave daughter of the king’s vizier who vows to risk her life in order that she might attempt to fix the king’s immoral ways.

This essay will discuss the importance of the role of Shahrazad, even though her portion of The Nights is based solely around her narration. Specifically, this argument will uncover the depth of Shahrazad’s character in relation to the role of Middle Eastern women around the time of the latter half of the twelfth century. Although Shahrazad’s role within The Nights is generally associated to be just narration, her storytelling methods can be analyzed through both a feminist and historical lens, making her influence within the progression of The Nights highly significant, both inside and outside of the frame. In fact, it is my argument that as a woman, Shahrazad conveys a sense of bravery beyond the norms for her society that no man can or does replicate. Through her storytelling abilities alone, Shahrazad displays a dignified sense of wisdom as she tells specific stories that make the king subconsciously reconsider his stance and ultimately, make her own story more significant than the many she tells. Finally, I discuss the significance of the role of Dinyazad, Shahrazad’s sister who spends her days within the bedroom with Shahrazad and the king, prompting her to keep telling stories. Without Dinyazad’s constant, verbal cues to her sister, would Shahrazad’s plan have been as effective?

Although the frame-tale begins with two dominant men, their stories are not the main focus of The Nights. Instead, once Shahrayar returns to his kingdom, Shahrazad, the vizier’s oldest daughter, takes control of the plot from here. Within the text, Shahrazad is described as a scholar:

The older daughter, Shahrazad, had read the books of literature, philosophy, and medicine. She knew poetry by heart, had studied historical reports, and was acquainted with the sayings of men and the maxims of sages and kings. She was intelligent, knowledgeable, wise, and refined. She had read and learned. (1182)

As an accomplished, educated woman, Shahrazad’s role within the story is monumental because it negates two common occurrences of the time in the Middle East: the status and education of women. According to Bernard Lewis, author of the book entitled The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2000 Years, “the emancipation of [Middle Eastern] women lags far behind changes in the status of men, and in many parts of the region is now in reverse” (17). Within the Middle Eastern society, women were given one of the lowest social statuses. In fact, their status was often equated with those of slaves and unbelievers, and “only the woman was, in the traditional religious world view, irredeemably fixed in her inferiority” (206). No matter what a woman did, because of her gender, her status was inevitably fixated. It was not until the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries that women’s roles within society began to change. During this time, the people of the Middle Eastern countries began to believe that “the education of women was necessary to save them from idle and empty lives, fit them for employment, and train them for harmonious marriages and the raising of children” (Lapidus 893). Therefore, the fact that Shahrazad is highly educated and serves as the narrator of The Nights defies the norms for Middle Eastern women of her time. Stemming from her education and social status, Shahrazad exercises a form of bravery that also negates the stereotypical characteristics of Middle Eastern women during the time. To put The Nights into context, the political network of the Middle Eastern societies during the twelfth century was heavily based on of the “just actions of men.” To explain, this meant that rulers believed that “they had the knowledge, understanding, and moral qualities essential to implement the revealed law,” while also obeying the law for themselves (Lapidus 183). Additionally, it was believed that only men had the right to be rulers, and thus, women were kept out of political affairs within society. Reiterating what was discussed earlier, until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Middle Eastern women held one of the lowest places within society. A woman’s voice was not considered valuable, and therefore, was generally not permitted to be heard within society (Lapidus 183). By challenging the king through narration, Shahrazad is consciously trying to change the role of women in the eyes of the law. Not only is Shahrazad acquitted with bravery, but her persistent actions symbolize how this bravery extends far beyond the capability of women of the time. When Shahrazad first introduces the idea of her sacrifice to her father, he tries his best to convince her to give up her plan. In fact, because he understands the likely consequence of giving his daughter up to Shahrayar, the vizier quickly grows angry, calling Shahrazad foolish and telling her to “Desist, sit quietly, and don’t expose yourself to peril” (1184). This scene clearly represents the vizier’s thoughts on bravery as he pleads with his daughter to simply live her life and let someone else take care of this problem within the kingdom. Shahrazad’s bravery does not sway, however, as she says, “Father, you must give me to him, even if he kills me…This is absolute and final” (1183). Shahrazad too understands the likelihood of what her plan could surmount to. The difference between herself and her father, though, is her willingness to sacrifice her own life to save others. With her education and wisdom, Shahrazad is potentially the only virgin living in the kingdom that understands how to go about changing the king’s perception of women.

Additionally, in the scene describing the encounter between the vizier and Shahrazad, the first glimpse of Shahrazad’s understanding of the power of voice is displayed. In one final attempt to convince his daughter not to give herself up to the king, the vizier tells Shahrazad two stories about what happens to people when they miscalculate their place in society. Shahrazad, though, is not effected by the stories and explains to her father what is going to happen if he does not grant her request: Such tales don’t deter me from my request. If you wish, I can tell you many such tales. In the end, if you don’t take me to King Shahrayar, I shall go to him by myself behind your back and tell him that you have refused to give me to one like him and that you have begrudged your master one like me. (1186) Here, Shahrazad’s bravery extends into disobeying her father’s wishes, despite his many authority and desperate attempts to change her mind. Clearly, Shahrazad understands the necessity of her actions and will not let anything, even her father’s pleas, deter her from doing the right thing.

When Shahrazad is indeed handed over to the king, she begins to craft a narration so precise that is humbles the king and eventually, after many nights, changes his mind on several issues. In fact, Shahrazad’s narration is such a unique, persuasive technique that several critics spend time analyzing it. According to feminist Fedwa Malti-Douglas in her article “Shahrazad Feminist,” Shahrazad “performs a critical role in changing the dynamics of male/female sexual relations, in redefining sexual politics. When she consciously takes on her shoulders the burden of saving womankind…she had taken on a much more arduous task: educating the ruler in the ways of a nonproblematic heterosexual relationship” (51). Rather than utilize the common strategies of men in power at the time, Shahrazad does not seek to lecture the king about his ways. Instead, through her narrative tactics, Shahrazad is trying to educate him. She understands the power of wisdom, and therefore, slowly and thoroughly teaches the king. Over time, her strategies make the king subconsciously reconsider his opinion, based on his reactions as the tales stretch on.

Because Shahrazad’s bravery and education are so clearly represented through her voice, the actions of the king are sometimes forgetten. Yes, being given the role of narrator is an uncommon opportunity for an Arab woman such as Shahrazad. And, through her meticulously thought out stories, it is not hard to tell that Shahrazad knows this too. Yet, what is even more curious is the way Shahrayar reacts to Shahrazad’s words. As a man of power, Shahrayar could have easily shut down Shahrazad’s plan when she came to the abrupt ending of her story the first night, and killed her like the rest of the virgins that came before her. And yet, he does not do this. Why?

Lydia Bandstra, Acrylic paint, 11″ x 15″

In contrast to Shahrazad, King Shahrayar does not inhabit a persona built on bravery. Whenever his authority is challenged, Shahrayar is so threatened that he overcompensates, typically resulting in an extreme reaction like self-pity or murder. For instance, when Shahrayar first learns of Shahzaman’s wife’s betrayal in the prologue of the tales, he immediately succumbs to an attitude of anger. Attempting to comfort his brother, Shahrayar says, “in my opinion, what happened to you has never happened to anyone else” (The Nights 1179). By saying this, Shahrayar is making it seem like his brother has been treated in a way that no man could have ever experienced besides Shahzaman himself. Yet, when Shahrayar suddenly learns that he himself is in the same situation as his brother, his attitude swiftly changes to that of self-pity and loathing, saying “no one is safe in this world…Perish the world and perish life! This is a great calamity, indeed” (1180). Because Shahrayar is now dealing with the same feelings of pain as his brother, within a very short amount of time, he assimilates this experience to all men and their relationships with women. Since, after all, Shahrayar is a king and would never be treated this unjustly were it not an experience that all men had to suffer through. Therefore, instead of bravely facing his kingdom in strength throughout this period of dishonor, Shahrayar cowers in defeat, declaring all women evil. Some critics, like Richard Van Leeuwen discusses within his article “The Canonization of The Thousand and One Nights,” believe that The Nights falls flat in terms of opportunities for character analyzation and overall significance. For instance, Van Leeuwen claims that an analysis of The Nights will only discover surface-level meaning:

The characters are puppets, they have no individual personality and the events are not the consequences of their decision, but rather of the vicissitudes of external fortune. There is no appreciation of the deeper realities of experience within individual man, and no sense of “real tragedy” …changes in fortune occur not through a direct effort of the hero, but as a result of coincidental circumstances. (106)

In this statement, Van Leeuwen suggests that the characters found within The Nights, such as King Shahrayar and Shahrazad, do not hold any significance outside of their normal, character routines. While Van Leeuwen poses an interesting argument, I must disagree with his thoughts. Had he analyzed the frame surrounding The Nights, Van Leeuwen would have better understood the goal of the stories included and thus recognized just how essential each character and his or her actions are to the overall effectiveness of The Nights. Perhaps it is not the goal of The Nights to include stories that make sense among society, but to challenge history. What if, by writing a text that is so different from traditional Middle Eastern tales, the author of The Nights planted the seed for a political or gender movement? In fact, it is not the characters within Shahrazad’s tales that are important, but rather, the king’s reaction to them. For instance, the patience of Shahrayar after Shahrazad’s initial tale signals that something is happening beneath the surface of the king’s mind than what first glance displays. Had Shahrazad not specifically planned her story to do this, Shahrayar would not have reacted this way, and thus, The Nights would not have concluded with the pair living in harmony.

Apart from Van Leeuwen, other critics challenge character roles within The Nights too, specifically in terms of who the true protagonist is. While it is my argument that Shahrazad serves as the narrator first and eventually turns into the protagonist, not all scholars agree. According to the Peter Heath, “the issue at stake is indeed Shahrazad’s life, but also that of Shahrayar. Besides, the central idea is now the restoration of the king’s sound perception both of himself and of women” (qtd. in Enderwitz 3). To add to that, scholar Mia Gerhardt believes that “the readers, like the compilers, gradually forget Shahrazad and her plight, and concentrate all their attention upon the stories she tells” (qtd. in Enderwitz 194). While Heath’s stance is correct about Shahrazad’s focus resting on repairing the king’s view of women, Shahrazad’s own story is not less significant than Shahrayar’s. With this said, Gerhardt’s point is disproved. Even though a reminder of Shahrazad’s role only happens when the tale of the night ends and the text once again reads “but morning overtook Shahrazad, and she lapsed into silence,” her survival remains the overarching focus. In fact, according to Eva Sallis, “‘It is Sheherazade’s life and narrative power which are remembered long after we become hazy about the myriad details of the contents”’ (qtd. in Enderwitz 189).Without Shahrazad, The Nights becomes a story with no purpose or significance – just a combination of tales that seemingly do not connect. Therefore, while Shahrazad inhabits the role of narrator, her plan gives her the title of protagonist, too.

The reason so much emphasis within the tales resides on repairing Shahriyar’s perception of women is due to Shahrazad’s wisdom. Up until her entrance into the king’s bedroom, the other women involved in the king’s plan have been uneducated virgins; no one that could challenge the king. Shahrazad’s knowledge, though, allows her to clearly think through the entire plan, and thus, she crafts a narration focused on addressing the king’s thoughts and actions directly. Through her precise narration, Shahrazad shows her recognition that the plot of her stories needs to be mainly focused on molding Shahrayar’s view on gender in a very specific way so as not to upset the king. Some critics, however, believe Shahrazad’s motives for narration are selfish. According to Fedwa Malti-Douglas in her article entitled “Narration and Desire: Shahrazad,” “from Shahrazad’s perspective, the frame becomes a ‘time-gaining’ technique, similar to other time-gaining or lifesaving acts of narration in the body of the Nights themselves” (11-12). While the method in which Shahrazad chooses to tell her story does increase the likelihood of her survival into the next morning, her main focus is not on saving her own life. From the very beginning of her plan, Shahrazad’s goal has been to save the people first, and then herself. In fact, she tells the vizier, “Father, you must give me to him, even if he kills me” (The Nights 1183). Here, she recognizes the likely consequence of her action, but through her selflessness and dignified sense of bravery, she pushes her fears aside and vows to carry out her plan for the people. Shahrazad’s method of storytelling is furthest from time gaining, it is a sacrifice – a potential suicide mission. As a result, each night Shahrazad tells the king a bit more of the captivating story she has constructed, peaking his interests and delaying her supposed death. Each portion of the story she tells has nothing to do with her own situation, yet, something about the tale always entices the king, allowing him to subconsciously reconsider his stance on women throughout the many nights Shahrazad spends with him.

The first story that Shahrazad tells to King Shahrayar is “The Story of the Merchant and the Demon.” Exercising her wisdom, Shahrazad uses this story to plant a seed of doubt in the king’s mind about mistakes – specifically his reaction to his wife’s affair. For example, in this tale, a merchant accidentally kills a demon’s son by throwing the pits of his dates on the ground. As a result, the demon immediately decides he must, in return, murder the merchant in order to avenge his son’s death saying, “I must kill you as you killed him – blood for blood” (1187). Shahrazad goes on to describe the merchant and the demon arguing back and forth as the merchant pleads for his life. Consequently, that first night ends with the story hanging in limbo – the demon’s sword raised and ready to strike down the merchant, but no inclination of whether he will.

Shahrazad tells this initial story because of who the fictional characters inside represent. Here, there are two characters with opposite statuses: the demon represents the power of the king, and the merchant represents the helplessness of women, both found in the situation of the king’s late wife and the kingdom’s virgins. Similar to the demon, King Shahrayar believed he had to kill his wife in order to compensate for her betrayal. Immediately upon finding out about her actions, Shahrayar uses his power to murder her rather than question her about her motives. Additionally, like the demon, Shahrayar’s mind is so hardened to the idea of trusting someone of a lower status, in this case women, that he immediately disregards any reasoning his wife might have to behave the way she did. Unlike the demon, though, Shahrayar acts quickly and not once falters in his decision to murder his wife. In fact, he goes so far as to vow to then sleep with a virgin each night before killing her the next morning. On the other hand, the merchant represents the helpless women within the kingdom. Like the merchant, Shahrayar’s late wife was accused of doing something to hurt someone in power, and the result was murder. More importantly though, the merchant represents the helpless virgins whose fate has been told to them countless times and yet, they cannot do anything about it.

There is a difference between the king’s situation and the fictional characters’ situation, though. By telling this specific story, Shahrazad is teaching Shahrayar what it looks like to exercise true wisdom and bravery. Instead of immediately killing the merchant, the demon listens to his pleas and in the end, gives the merchant one year to say good-bye to his family. The demon did not know if the merchant would actually return, and yet, he chose to grant the man’s request anyway. When Shahrazad ends the tale unconcluded and with no hint as to what might happen next, the king is captivated, “burning with curiosity to hear the rest of the story” (1188). Although Shahrazad used a simple method of metaphorical storytelling, the king yearns to hear the conclusion of the story, meaning that something within Shahrazad’s words has penetrated his hardened heart. In fact, the king is so consumed by the story that the first thing he asks of Shahrazad the next night is for the conclusion to the story of the demon and the merchant.

Additionally, the first act of bravery displayed by a man is found inside of this first tale that Shahrazad uses, also represented by the merchant. Subtly, Shahrazad brings up the issue of bravery by introducing several fictional male characters in this story alone that inhabit this persona. For example, although the demon immediately tells the merchant he must kill him after he finds his son dead, the night does not end in another death. Instead, the merchant refuses to give up on his life and pleads for forgiveness. Here, the merchant represents a man of bravery because of the sense of humility he displays as he recognizes his mistakes and humbly asks the demon for forgiveness. Had the merchant cowered in defeat, much like King Shahrayar, the outcome would have likely been his death. Instead, though, the merchant displays his knowledge of the power of voice, pleading with the demon to at least give him a chance to say farewell to his family. Then, a furthered sense of bravery is displayed by the merchant when, after one year, he willingly decides to return to the demon’s home. When this time comes, the merchant’s family is tormented by sadness, but still he keeps his promise. “He said to [his family], ‘Children, this is God’s will and decree, for man was created to die.’ Then he turned away and, mounting his horse, journeyed day and night until he reached the orchard on New Year’s Day” (1189). Understanding the importance of bravery, the merchant remains faithful to his promise, even though he could have easily hidden himself in his home and forgotten about the demon.

It is no surprise that male bravery does not show up in The Nights until Shahrazad’s fictional tales. The purpose of Shahrazad’s character, the merchant, centers around the idea that bravery is not gender or class specific, but rather depends upon personality, wisdom, and overall faithfulness. Additionally, Shahrazad is quite precise about the way she introduces the idea of pure bravery to King Shahrayar. Had she outright belittled the king’s bravery, or, used any sort of female character within her story, her point would not have been made. King Shahrayar represents a generation of men who believe that their lives matter more than others, that power is everything, and that female importance is nonexistent outside of the bedroom. The king cannot be challenged by a woman outright, nor will he be accepting of accusations pulled from a real-life event because of his power. Therefore, the only way to get Shahrayar to relate to a story was for Shahrazad to use fictional male characters. Shahrazad displays her awareness of her specific audience through the stories she uses, and the order of which she tells them. Additionally, because Shahrazad knows how difficult it will be to change the king’s view, her bravery is further demonstrated as she decides to take on the challenge anyway. For the rest of The Nights, Shahrazad exercises this method of oral storytelling, which in turn displays her sense of wisdom. In fact, Shahrazad seems to have picked the perfect strategy necessary to execute her plan of saving the people. According to Enderwitz:

a speech in a way of a theologian or philosopher would have been useless [for Shahrayar]… He was in need of a knowledge that is supplied only by experience and literature, a knowledge comprising human totality, body, soul, sentiment…Therefore, Shahrazad instructs by way of narration. (qtd. in Enderwitz 196)

Each night, Shahrazad adds an aspect to her story that subtly furthers the king’s interests and changes his mind through education. For example, it takes Shahrazad eight full nights to finish her initial tale because of the caution she takes when introducing each new character and his story to the king. Had she taken another, perhaps quicker, approach, Shahrayar’s domineering personality would not have been accepting of her ways, resulting in death come sunrise. Here, Shahrazad presents her understanding of the key relationship between storytelling and politics, which, in harmony, can translate into power. According to Melissa Matthes, “a skillful narrative invites the listener into its world, forming a bond of engagement between the two. A story can also bring forward the assumptions buried in apparently neutral arguments and challenge them” (79). Shahrazad does just this in her mode of storytelling, inviting the king, without his realization, to rethink his assumptions of women through her use of fictional characters living in an imaginary world. And, because of this “skillful narration,” by the end of The Nights, Shahrazad succeeds in changing the king’s opinion and ultimately, enables him to fall in love with her.

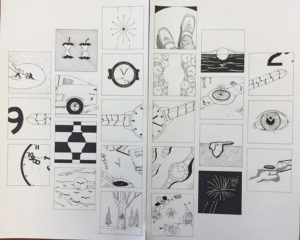

Ian Meentemeyer, pen and ink, “Watch”

Apart from Shahrazad, another woman should be recognized for bravery and wisdom in The Nights: Dinyazad. Each night Dinyazad continuously reminds Shahrazad of the importance of timing, and keeps the king curious based on her own interest in the continuation of the tales. Although her role within the tales only makes an appearance when dawn and dusk arrive, the outcome where Shahrazad lives and the king has fallen in love would not have happened. From the beginning of The Nights, Shahrazad recognizes the importance of Dinyazad’s presence in the bedroom. She tells Dinyazad, “When I go to the king, I will send for you, and when you come and see that the king has finished with me, say, ‘Sister, if you are not sleepy, tell us a story.’ Then I will begin to tell a story, and it will cause the king to stop his practice, save myself, and deliver the people” (The Nights 1186). Rather than allow the burden of saving the women of the kingdom to rest solely on her own shoulders, Shahrazad splits the weight between herself and Dinyazad. Here, Shahrazad shows understanding for the power of voice combined with the power of women as she incorporates her sister into her plans.

Shahrazad and Dinyazad represent the spectrum of women found within The Nights. For instance, while Shahrazad is described as having a lengthy, scholarly education, not once is Dinyazad’s wisdom or importance mentioned prior to the tales. Additionally, Dinyazad’s sole purpose within the story seems to rest in the hands of her sister. Had Shahrazad not called upon Dinyazad, there mostly likely would not have been any mention of her. Yet, despite her lack of education or worldly awareness, Dinyazad immediately submits to Shahrazad’s request when she is asked to participate in her plans, replying with “Very well” (1186). In fact, even though Dinyazad likely understands the role of women within her society, not once does she question Shahrazad’s motives. In her own way, Dinyazad serves as the heroine of The Nights. Dinyazad’s role within Shahrazad’s tales is so important that without her voice, each night would not begin, nor would each morning end. Patiently, Dinyazad sacrifices her time to wait in the bedroom night after night, only revealing herself when necessary to push that night’s tale further along. In this way, Dinyazad watches over her sister, making sure that the plan is progressing accordingly. Dinyazad keeps Shahrazad conscious of her purpose, and how effective voice can be when appropriately timed and utilized.

Few scholars have taken the time to dissect Dinyazad’s role within Shahrazad’s tales, but it is my belief that a complete feminist analysis of The Nights cannot be done without acknowledging her. For example, Enderwitz describes the sisters’ relationship as dependent upon each other for survival: “the privileged and emancipated Shahrazad…cannot free herself as long as the poor, uneducated, and veiled Dunyazad in her traditional setting remains in subjugation or…that the freedom of the former is at the expense of the latter” (198). What Enderwitz argues here is that had Shahrazad’s plan failed, Dinyazad would have likely died alongside her. While I agree with Enderwitz’s idea, I would argue that she is missing an essential component of Dinyazad and Shahrazad’s relationship. Like Shahrazad, Dinyazad consciously lays down her life to serve others by agreeing to her sister’s request. However, is Dinyazad’s sacrifice not more crucial than Shahrazad’s? Because Dinyazad is not used by King Shahrayar for anything inside of the bedroom, does her life not hang in limbo the entire time that Shahrazad speaks? For example, were the king to disagree with and lash out at part of Shahrazad’s tales, Dinyazad’s life would likely be the first to feel the brunt of his anger, rather than Shahrazad. To explain, the entire time the sisters spend in Shahrayar’s bedroom, Dinyazad’s life is completely disposable. She serves no purpose outside of the plan, such as a sexual partner or storyteller, and therefore, could easily be killed by Shahrayar. Additionally, without Dinyazad’s involvement, the plan would not have taken off in the first place. The success of The Nights is directly contingent upon the character Dinyazad, not Shahrazad. Although it is Shahrazad’s voice that propels us through tale after tale, it is Dinyazad who opens the door to allow her to do so. There is not one brave woman within The Nights, but two.

Overall, in this essay I have argued that the role of Shahrazad extends beyond the simple title of narrator. Through her actions, Shahrazad displays a sense of bravery and wisdom that extends beyond the characteristics of a Middle Eastern woman during the twelfth century. As she utilizes precise narrative techniques, Shahrazad educates King Shahrayar about his incorrect perception of women, ultimately changing his views by the end of The Nights. Additionally, through the analysis of King Shahrayar himself, I have come to the conclusion that Shahrazad’s actions are not and could not be replicated by any human man found within The Nights. Through her display of bravery and wisdom, Shahrazad transforms The Nights into an educational lesson for the king, and through this method, ends up saving both herself and the people of the kingdom. Therefore, even though Shahrazad is seen as only the narrator, her stories propel her into the role of protagonist, too, making her own tale more significant than the many she tells to the king. Finally, I have discussed the too-often-ignored importance of Shahrazad’s uneducated sister, Dinyazad, claiming that without her extraordinary sacrifice, Shahrazad’s voice would never have been heard by the king.

Works Cited

Enderwitz, Susanne. “Shahrazâd Is One of Us: Practical Narrative, Theoretical Discussion, and Feminist Discourse.” The Arabian Nights in Transnational Perspective, edited by Ulrich Marzolph, Wayne State UP, 2007, pp. 261-275.

Lapidus, Ira M, and Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge Cambridgeshire, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Lewis, Bernard, and Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. The Middle East : A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. New York, N.Y., Scribner, 1995.

Malti-Douglas, Fedwa. “Narration and Desire: Shahrazad.” Woman’s Body, Woman’s World. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press, 1991.

——. “Shahrazâd Feminist.” The Arabian Nights Reader, edited by Ulrich Marzolph, Wayne State UP, 2006, pp. 342-64.

Matthes, Melissa, “Shahrazad’s Sisters: Storytelling and Politics in the Memoirs of Mernissi, ElSaadawi and Ashrawi,”Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, vol. 19, no. 19, 1999, pp.68–96.

“The Thousand and One Nights,” The Norton Anthology of World Literature, edited by Martin Puchner, shorter 3 rd ed., vol. 1, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, pp. 1176-1197.