Robert Henri and the Ideal Woman: An Analysis of Ballet Girl in White

By Fynn Wadsworth ’25

ART 325 Modern Art & Architecture

Fynn’s great strength here builds from an exceptionally keen eye for visual evidence that supports a compelling thesis. His nuanced analysis of the painting, together with primary and secondary sources, offers convincing support for the argument that, counter to stereotypes of the ballerina broadcast through popular culture in the early 20th century that often contributed to their marginalization and exploitation, Robert Henri’s painting Ballet Girl in White (ca. 1909), presents a fully realized individual “in all her imperfect, human glory,” showing us a picture that refuses to participate in the mistreatment of these women.

-Dr. Susan Wight Swanson

In the early 1900s, artists were still largely defining who and what was worth documenting and drawing attention to. The upper classes still dominated the art world and while many artists were frequently depicting the lower classes in their work, they were still largely stigmatized subjects. The poor, especially poor women, were often romanticized in artists’ depictions, and yet were often being exploited by the very artists who were painting them. These women came in many forms, from factory workers to seamstresses but none were as sexualized and romanticized as the women of entertainment. The dancer and the performer became an easy target for artists looking for a subject that could be exploited both artistically and sexually. In contrast, Robert Henri’s painting Ballet Girl in White (1909) (Fig. 1) along with many of his other portraits of poor and working women, place these women away from their stigmatized professions, and does not depict them as simply a body, but instead, as an entire being. In doing this, Robert Henri goes against how early twentieth-century America viewed not only the dancer, but women as a whole. Robert Henri paints a more human version of the modern woman, versus an idealized one that serves the public instead of the girl herself.

To begin, artist Robert Henri, previously Robert Henry Cozad, was born on June 24th, 1865 to John Cozad and Theresa Gatewood. Henri and his family fled his birth state of Nebraska for Colorado after Henri’s father shot a man in the local grocery store over gambling money to avoid charges.1 The family, with new identities, then fled east to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where they would settle. He had an interest in art from a young age but did not consider making it a career until around 1885.2 He would later study at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. While attending the Academy in Pennsylvania, he also studied for a semester at The Académie Julian in Paris.3 He found much inspiration in both of the teachers he studied under in Paris and in Venice, as well as many of the Paris Salons that he both attended and exhibited in during his time in France.4 Around 1891, Henri returned to America and began a career in teaching.5

Hence, in 1892, Henri would be offered a teaching position at the Women’s School of Design, also known as the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, where he stayed for several years. The school taught over two-hundred women at Henri’s time, and despite still relying heavily on the teaching of skills considered “women’s work,” the school taught many formal painting and drawing classes.6 Henri would instruct drawing from the Antique, artistic anatomy, and composition courses, and would go on to be one of the most influential teachers competing before the Modernist period, having taught dozens of the most influential women of the movement, as well as hundreds of other female artists of the period.7 Henri emphasized how beauty was subjective in his teaching, which must have resonated with a lot of female students. In his own writing, he addresses the School of Design students with this, “Thus two individuals looking at the same objects may both exclaim ‘Beautiful!’ — both be right, and yet each have a different sensation — each seeing different characteristics as the silent ones, according to the prejudice of their sensations. Beauty is no material thing. Beauty cannot be copied. Beauty is a sensation of pleasure on the mind of the seer.”8 In other words, Henri largely believed that beauty came in all forms and that it appeared different to everyone, which gave way to a teacher who could resonate with many different students’ works. In addition, Henri’s emphasis on beauty and its subjectivity also aligns with the Ashcan School movement’s take on Impressionism. Henri pioneered this style of art known as the “Ashcan School,” with its mix of artistic movements that included elements of Realism, Impressionism, and Post Impressionism, coupled with depictions of the lower classes, urban environments, and cityscapes that most other artists avoided.9 Henri, true to Ashcan ideals, rejected many of the traditional ideas of Impressionism specifically. He favored a darker and desaturated color palette and disliked the prettiness or “holiday atmosphere” of artists like Claude Monet or Childe Hassam.10 This dislike of Impressionism would lead Henri to become one of the main contributors to the aforementioned Ashcan School movement, where he and seven other contemporaries and friends would continue to promote their own ideas about Impressionism and art in general, as well as exhibit and teach together.11

To elaborate further, Ashcan School artists would focus on urban settings and the poor and underrepresented people within them, as well as favoring a darker, richer color palette in their works, while still utilizing the more expressive qualities of Impressionism. The movement of Impressionism itself focuses on depictions of nature, air, and light, something that artists like Henri would contort in order to express an Ashcan sensibility. In other words, he used these ideas as a base to depict the more raw, gritty setting of urban America.12 In his article “Ashcan Perspectives,” art historian David Corbett notes the visual approach taken by the Ashcan artists, writing, “Commenters on the Ashcan artists have most often seen them as the visual equivalents of Walt Whitman, that is, poets of the humanity and dynamism of the streets whose urban realism provided a visual language for those qualities.”13 Strictly speaking, Corbett argues that the Ashcan artists are

paving the way for the people of poor, urban communities within the art world through their blend of realism and Impressionist aestheticism. The Ashcan take on art focuses heavily on the urban and poorer areas of twentieth-century America and sought to portray these areas as beautiful and as fully as any other place in the world. The movement continues the Impressionist focus on plein air painting but with a focus on not just urban area landscapes, but on portraying the people residing in them. Many of these painters, such as William Glackens or John Sloan, have large bodies of work that exist somewhere between landscape and genre painting, just as it exists between Realism and Impressionism. Robert Henri himself would describe the people depicted in his paintings as “His People,” writing “Everywhere I see at times this beautiful expression of the dignity of life, to which I respond with a wish to preserve this beauty of humanity for my friends to enjoy.”14

Comparatively, Robert Henri’s painting Ballet Girl in White (Fig. 1) is a very good example of both Ashcan School sensibilities and Henri’s personal beliefs about beauty and humanity. Henri cared very deeply about the details of his paintings, saying, “The lace on a woman’s wrist is an entirely different thing from the lace in a shop. In the shop it is a piece of workmanship, on her hand it is the accentuation of her gentleness of character and refinement.”15 His attention to these kinds of details adds much of the needed intricacy to fully bring the Ballet Girl to life. The painting itself features a figure of a young, female ballet dancer, posed in 5th position with her hand clasped at her waist. Her dress is white and has a full skirt ending just above her knees. She wears white tights and a pair of light pink ballet shoes. She has a garland of leaves over her left shoulder, and puffy, white flowers in her hair. The room she stands in has a brown back wall and dark floor, with no furniture or other objects in view. The figure is painted on a large, long canvas that makes the dancer just above six feet tall. Her color palette consists of a selection of warm grays, pinks, and greens, with a few hints of a dark navy or black in some sections. The paint itself is very textured and thick in sections, with a few choice spots of heavy, mixed tone blotching. Her features sometimes fade into each other or into the background, while others are heavily contrasted with thick, dark paint.

The figure holds herself very firmly, holding back from the viewer in the shallow, empty space she’s painted in. Her hands being clasped in front of her and her eyes looking off into the distance give a feeling of reserved sadness, with her slumped body language adding to this feeling. Her feet are pointed but her body is not tense. She lacks the precision we often associate with a ballet dancer, instead she appears quite dejected as she looks past the viewer into the distance. In the same way she lacks movement, she also lacks the luster of being shown on stage. Her body or her artistic expression is not the focus of Henri’s work, instead it is simply the girl herself. His dancer also features the harsh shadow looming behind her, an embodiment of the shame or sadness she seems to hold. Harsh lighting plays up both her pale skin and her white dress. The lightness of the painting creates a feeling of innocence or softness in the figure, while the harsh shadows and splashes of dark color throughout her tutu and in her hair contrast the lightness with darkness. This makes the figure feel more rounded, her thoughtful expression and dark eyes coexisting with her youth and softness. Henri’s Ballet Girl puts emphasis on all of these parts at once, in turn putting the emphasis on the dancer as a person rather than just a figure. The way she holds all of these negative emotions in her demeanor and in her face create an image of the dance that looks deeper than her profession or her reputation. She is as much a dancer as she is human.

This contrasts with other popular depictions of ballerinas, notably those painted by Edgar Degas. I chose Degas’s Dancer in Front of a Window (Dancer at the Photographers Studio) (1873-1875) (Fig.2) specifically to contrast Henri’s Ballet Girl in White (Fig.1) because of their similar compositional elements. These paintings at first glance appear almost identical. They both feature a ballet dancer alone, in a very empty space and in their tutus, but this is truly where the comparisons end. The life and warmth depicted in Henri’s Ballet Girl is completely missing in Degas’s Dancer, where the figure’s harsh and rigid movement pairs well with her expressionless face. The cool blues and greens of Degas’s work bathe the figure in a dusky light that makes the dancer herself almost fade into the gray cityscape behind her. She holds the same darkness as Henri’s figure but instead of adding a depth to the figure, the darkness instead flattens her further, as the deep blue tones and harsh angle of the floor continue to plateau the painting. These flat aspects are something many of Degas’s ballerinas share, where they are often being shown to the viewer almost as if they were at a distance on a stage. Degas’s dancers are not allowed the intimacy or depth we see in Henri’s interpretation.

Yet, Degas is well known for his portrayals of the ballerinas, and twentieth-century dance critic Boris Kochno even claimed that “the ballet dancers had found their painter” in Degas.16 Degas himself, as well as many other men in association with ballet during the era, have been found by scholars to have personally exploited the dancers they so loved. Ballet itself took a harsh shift in the late nineteenth century that turned ballet from the beloved, genderless dance art into a wholly erotic and effeminate practice, in which the male dancer was viewed as contaminating and disruptive.17 The female dancer, on the other hand, was now seen as a symbol for beauty, femininity, and promiscuity. Further, the ballerina was often a daughter of a lower-class family, who sometimes chose the profession, or on rare occasions, was sold into it.18 These women’s position, both in society and as sex symbols, created a very exploitative environment for the girls, who were often very young in age. Due to this, the lower-class girls of ballet were being sought out for sexual consumption by middle- and upper-class men.19 Degas was complicit in this in many ways, with his paintings taking the ballet dancer and conforming her to her stereotype, as historian Ilyana Karthas notes about Degas’s dancers, “In his work, the ballet dancer was no longer a metaphoric symbol of nobility, grace, or poetry, but rather conceived first and foremost as a sexual being, a worker, and a titillating subject.”20 These paintings often portray the girls as something to be both admired and objectified. The flat, cold paintings shape the girls into permanent sex symbols, and in turn somewhat reflect the real life of a ballet dancer just as Henri’s paintings do, but with none of the humanity or dignity of Henri’s portrait. Even in a standalone portrait such as Dancer in Front of a Window (Fig. 2) that removed the audience that is often present in Degas’s ballet paintings, the girl is still a vessel for others to project their thoughts on to. She is as flat as a blank slate, something that molds and bends for a paying audience instead of for her own passions or desires. As literary theorist Charles Bernheimer describes, “The grimacing body — distorted, disarticulated, unstable, even inverted — this ‘reconstructed’ body of ‘the female animal’ is the victim of Degas’s misogyny.”21 The way Degas forces his dancers into the stiff, unmoving ballet poses removes them from their humanity and pushes them even further into being nothing but a pretty object. Henri’s painting, in contrast, takes the dancer and removes her almost entirely from her position as a sexual object, or even as a dancer. She stands posed, but in a way that allows her to draw back from the viewer in a way the allows her privacy, versus covering her in a romanticized sheen as Degas tends to. Her unidealized, slumped body allows her more privacy as well, pulling her further away from her sexualized position in society and allowing her room to breathe away from the gaze of an objectifying audience. Degas’s exploitations of the ballerina compared to Henri’s respectful portrayal in Ballet Girl in White show two very different sides of the ballerina, and I would argue that one clearly shows her more respect and that option is clearly Henri’s.

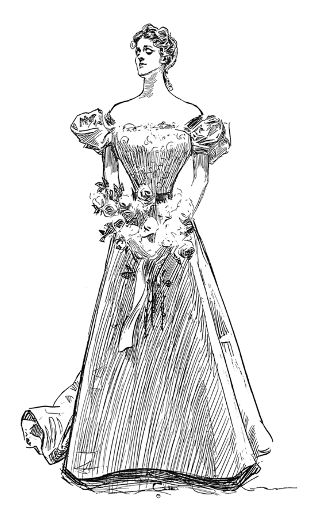

Similarly, another artist of the period was depicting the idealized woman, although not through the context of ballet. Charles Gibson, the man behind the “Gibson Girl” who would dominate advertising and popular culture in the early twentieth century, created his “girls” to be quite similar to Degas’s, although appealing mostly to a female viewer versus a male one. His girls are idealized in a more prim and proper way than Degas’s, or as described by Gibson’s friend Richard Davis, “Gibson has always shown her as a fine and tall young person, with a beautiful face and figure, and with a fearlessness on her brow and in her eyes that comes from innocence and from confidence in the innocence of others towards her.”22 The Gibson Girl became an American ideal, with women across the country striving to the standard set by this idealized woman portrayed in Gibson’s sketches and publications (Fig. 3).23 Whereas Degas was portraying an ideal sexual fantasy for a male audience, Gibson was creating an ideal woman who could be a figure for the modern woman to look at and emulate. This could lead to a belief that Gibson was just as far away from the portrayal of women as Henri sets forth, but instead, they both seem to slightly alter what is expected of women in the period. As Davis continues with his interpretation of his friend’s work, he says, “But with all this evident admiration for the American woman Gibson is somewhat inconsistent. For he is constantly placing her in positions that make us fear she is a cynical and worldly-wise young person, and of a fickleness of her that belies her looks.”24 Both Gibson and Henri portray a woman as much more than a pretty face in this way. Gibson’s girls have an air of

confidence and self-assuredness that is as equally lacking in Degas›s work as the subtle sadness that is present in Henri’s work, Ballet Girl in White. Henri’s own assertion that a pretty face is dull and empty25 could make Gibson’s work something Henri would not have found a resemblance in, but I think they are more alike than different.26 Many of Gibson’s illustrations are also stand-alone women like in Henri’s portrait. In Gibson’s work, these women are often depicted simply standing, often with their hands placed comfortably in front of them or against their hip just as Henri’s Ballet Girl clasps her hands in front of her. They are posed and sometimes face the viewer as in the Gibson Girl from 1900 (Fig. 3). Unlike Henri’s portrait, this woman is shown head high, holding her flowers with pride, almost disregarding the viewer because of her own perceived importance. Her shoulders are high while Henri’s dancer slumps into herself. Henri’s dancer and Gibson’s worldly woman portray contradicting emotions, and yet both create a sense of personality and underlying feeling that gives both women a depth of character instead of becoming just another portrait of a beautiful woman or another sexual fantasy. Both women are allowed depth, but Henri’s figure still portrays a more realistic modern woman. The Gibson Girl is allowed depth and dignity, but she is still a constructed ideal. The Ballet Girl in White is a real woman, although we do not know her. The perfection of the Gibson Girl is truly her downfall, as she is not just one perfect girl, she is hundreds of them.

To conclude, the authenticity in Henri’s portrait is aided by his ballerina being a standalone portrait, and furthermore, one that is allowed imperfection. The rough, splotchy paint of Henri’s Ballet Girl aids in making her feel multi-dimensional in a way Gibson’s illustrations cannot. Degas utilizes texture in Dancer in Front of a Window, but it lacks the depth of Henri’s tones. Both Degas’s paintings and Gibson’s illustrations also lack the scale of Henri’s portrait. The lifelike size of Ballet Girl in White almost adds to her humanity in that you can look at her as you would another person, whereas Degas’s painting forces intimacy in its scale just as Gibson’s illustrations do. Further, the warmth that exudes from Henri’s work is simply not present in the other men’s works, where the flatness does not allow for the same intimate understanding of the figure. You can get to know Ballet Girl in White in a way that is not allowed in the work of Degas or Gibson, both of which have a shield of idealization and expectation wafting over them.

The painting Ballet Girl in White is simple yet gives so much depth and understanding to an otherwise misunderstood and overly idealized group of people. The early-twentieth-century woman is allowed very little room to move or grow within Edgar Degas’s or Charles Gibson’s works. In contrast, Henri’s portrait allows for an exploration of a woman who is both beautiful and sad, poised, and dejected, and is portrayed as an entire, whole being. The flatness of the other works makes the rounded fullness of Henri’s portrayal all the more evident. His respect for not only the woman he paints, but the women he teaches comes through in this work and allows a more human version of the modern woman to be put into the forefront of the art world, even for a moment. As Robert Henri himself says, “Beauty is never dull and it fills all spaces,” and I believe this sentiment rings true in Ballet Girl in White.27 She truly does fill all space, in all her imperfect, human glory.

Fig. 1

Robert Henri (American, 1865-1929) Ballet Girl in White, 1909

oil on canvas, 76 7/16 x 36 7/8 inches (194.2×93.7 cm)

Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections, Gift of the Des Moines Association of Fine Arts. 1927.1

Photo Credit: Rich Sanders, Des Moines

Fig. 2

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) Dancer in Front of a Window, 1873-1875

oil on canvas, 25.5 x 19.7 inches (65×50 cm)

Pushkin Museum, Moscow. Inv. GMNZI: 39

Due to image restrictions, painting may be viewed at the following link.

http://www.newestmuseum.ru/data/authors/d/degas_edgar/dancer_posing_for_a_photographer.php

Fig. 3

“Special Exhibit,” detail of an illustration from Sketches and Cartoons by Charles Dana Gibson, 1900.

Ink on paper. Public domain.

1 Bennard Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, (Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc., 1991), 5.

2 Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, 6.

3 Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, 11 – 16.

4 Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, 18.

5 Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, 24.

6 Pearlman, Robert Henri: His Life and Art, 24.

7 Marien Wardle, American Women Modernists, (Provo: Brigham Young University Museum of Art,

2005.), 4.

8 Robert Henri, The Art Spirit, ed. Margery A. Ryerson (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1923), 79.

9 Richard Boyle, American Impressionism, (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1982), 44.

10 Boyle, American Impressionism, 218.

11 Boyle, American Impressionism, 218.

12 Wayne Morgan, Victorian Culture in America 1865 – 1914. (Itasca, NY: F. E. Peacock Publishers, Inc.), 23.

13 David Corbett, “Ashcan Perspectives,” American Art 25, no. 1, (Spring 2011): 14.

14 Henri, “My People,” The Craftsman 27, no.5 (February 1915): 459.

15 Henri, The Art Spirit, 124.

16 Ilyana Karthas, The Politics of Gender and The Revival of Ballet in Twentieth Century France, Journal of Social History 45, no. 4 (Summer 2012): 964.

17 Karthas, The Politics of Gender and The Revival of Ballet in Twentieth Century France, 965.

18 Deirdre Kelly, Ballerina: Sex, Scandal and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection, (Canada: Greystone Books, 2012), 14.

19 Charles Bernheimer, “Degas’s Brothels: Voyeurism and Ideology,” Representations, no.20 (August 1987): 159.

20 Karthas, The Politics of Gender and the Revival of Ballet in Early Twentieth Century France, 961.

21 Bernheimer, “Dega’s Brothels: Voyeurism and Ideology,” 159.

22 Richard Davis, “The Origin of a Type of American Girl,” The Quarterly Illustrator 3, no. 9, (Jan. – Mar.

1895), 6.

23 Davis, “The Origin of a Type of American Girl,” 6.

24 Davis, “The Origin of a Type of American Girl,” 6.

25 Henri, The Art Spirit, 124.

26 Henri, The Art Spirit, 124.

27 Henri, “The Art Spirit,” 124.

Works Cited

Bernheimer, Charles. “Degas Brothels: Voyeurism and Ideology.” Representations 20: Special Issue: Misogyny, Misandry, and Misanthropy. (Autumn 1987): 158 – 186

Boyle, Richard. American Impressionism. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1982.

Corbett, David Peters. “Ashcan Perspectives.” American Art 25, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 13-15.

Davis, Richard Harding, and Charles Dana Gibson. “The Origin of a Type of the American Girl.” The Quarterly Illustrator 3, no. 9 (January – March 1895): 3-8.

Gibson, Charles Dana. Sketches and Cartoons by Charles Dana Gibson. New York: R.H. Russell, 1900. Public domain through Gutenberg.org. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/62920

Henri, Robert. The Art Spirit. ed. Margery A. Ryerson. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1923.

Henri, Robert. “My People.” The Craftsman 27, no. 5 (February 1915): 459 – 469.

Karthas, Ilyana. “The Politics of Gender and the Revival of Ballet in Early Twentieth Century France.” Journal of Social History 45, no. 4. (Summer 2012): 960-989.

Kelly, Deirdre. Ballerina: Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection, Vancouver Canada: Greystone Books, 2012.

Morgan, H. Wayne. Victorian Culture in America 1865–1914. Itasca: F. E. Peacock Publishers, 1973.

Perlman, Bennard B. Robert Henri: His Art and Life. Mineola: Dover Publications, 1991.

Wardle, Marian. American Woman Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri, 1910-1945. Provo: Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 2005.